Article by Steve Frankham. Photos by Steve Frankham and Farhan Jihem

INTO ANOTHER WORLD

Our small motorboat is rolling gently in a glassy emerald sea. Just beyond rises the rocky sculpted form of Ko Sarang, a small island within the Ko Tarutao National Park in Southern Thailand. To the North, framing a group of other small islands, rises the rainforest-clad slopes of another, much larger island, Ko Rawi. Me and my fellow divers, including my dive buddy and divemaster Sean, make our way to the boat’s gunnel. Making some last checks, we inelegantly backroll into the warm sea. At 30֯C, it’s pretty much the same temperature as the air. With a downward thumb signal from Sean, we descend into another world.

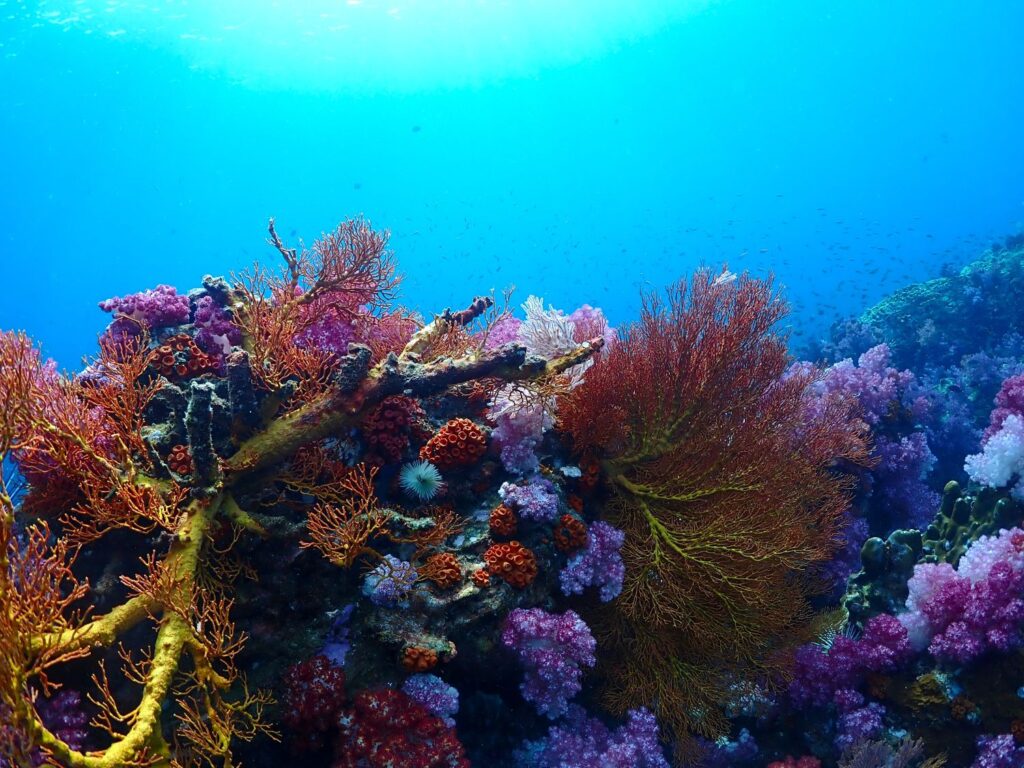

The rocky landscape of Ko Sarang continues below the surface, with huge boulders forming walls, canyons, and crevices. Here, below the surface, the boulders are crowded with life, covered with a mesmerizing diversity of soft and hard corals, anemones, and delicate feather stars, which in turn provide homes to clouds of colourful fish that wave and shimmer in the current.

UNDER THE SPELL OF THE DEEP

When diving, I seem to enter a state of almost ‘mindful meditation’. I’m freed from gravity, able to fly like an eagle over this wonderful marine landscape. I give myself entirely to observing and absorbing the beauty around me, and all other concerns seem to melt away. I find myself constantly fascinated and curious, staring into huge purple barrel corals, curious of its inhabitants, or enchanted by a pair of clownfish as they busy themselves with maintaining their anemone home. This curiosity doesn’t just go one way. Many times I look up to see myself being studied by an inquisitive porcupine fish, or highly territorial triggerfish, wondering who or what is this strange intruder into their underwater realm.

SEA MONSTERS

Drifting over some plate corals I notice the form of a true monster, a giant moray, the biggest I have ever observed, sinuously swimming through the cracks and tunnels beneath the coral. He’s probably two and a half meters long, but entirely benevolent unless recklessly provoked. It’s an awe-inspiring sight.

I am impressed by the health of the corals, and especially the soft corals, which sway in fields on the surface of the rocks, in gentle tones of purple and white. When we surface, Sean, who has been an instructor here for many years, tells me the soft corals in this part of the National Park, the ‘far islands’ have actually improved. It’s an encouraging sign, but this is not the whole story.

KRIS

I’m here in Ko Tarutao to see how coral reefs are faring in the face of human-caused climate change, pollution, and potentially the side effects of tourism. I’m also here to see if scuba divers, and tourism based around the diving industry, can actually have some positive effects on this complex marine eco-system.

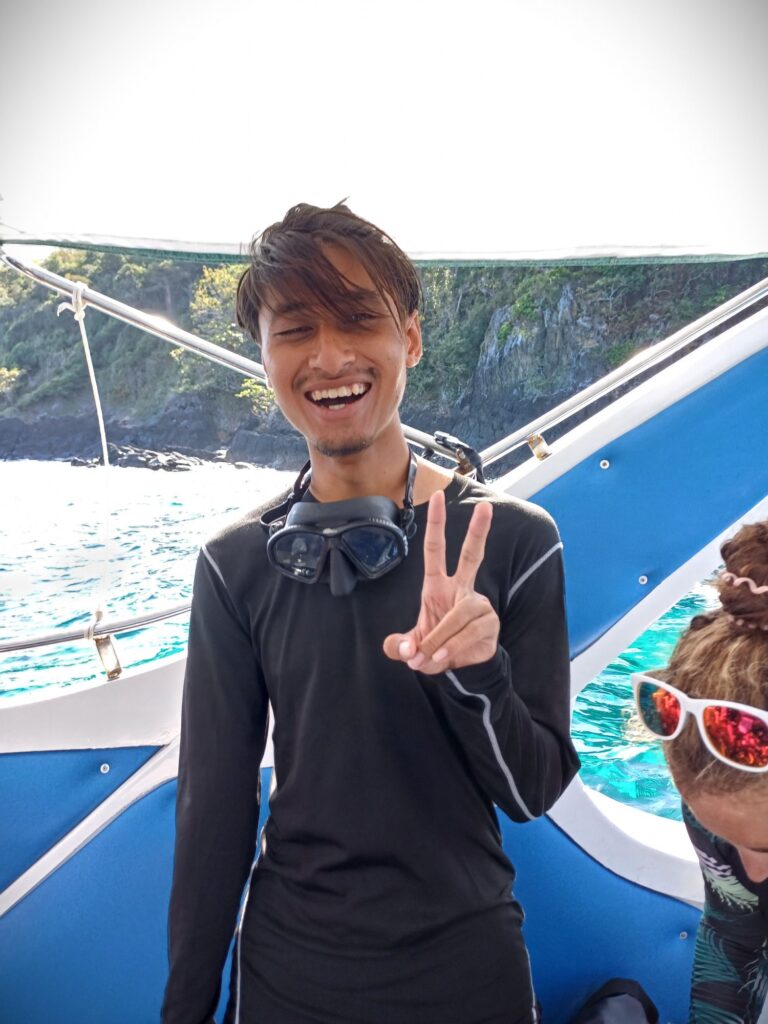

Helping me with this project are small local company Adang Sea Divers, run by its welcoming owner, Kris Scope. Kris has been diving and working in Ko Tarutao for many years. He is actively involved in the conservation and protection of these reefs, which are some of the healthiest remaining in Thailand. Kris is a handsome, laidback type, who seems to be a natural for beach life, but comes over as observant and thoughtful at the same time.

CHANGING LIVES

I sit down with Kris at his dive school on Sunrise Beach, Ko Lipe. It’s a beautiful spot. Traditional Thai ‘longtail’ boats loll in the turquoise water, palms sway gently in the breeze, and the much larger mountainous bulk of Ko Adang, the park’s second-largest island, looms just to the north.

Ko Lipe is the only ‘inhabited’ island in the Ko Tarutao National Park. Only a few kilometres long, Lipe has long been the home of the Chow Ley, a traditionally nomadic ethnic group whose lives have long revolved around fishing. In recent years the lives of Chow Ley have changed rapidly, with an explosion of tourism on the island. This has brought both positive and negative changes for the population. Positive in the form of jobs and education (many of Kris’s instructors and boatmen are Chow Ley), but also challenging, in the sudden lifestyle change this has brought.

STORM CLOUDS ON THE HORIZON

This place is still paradise, but the storm clouds are on the horizon, and Kris has witnessed some frightening changes. Up until the summer Spring/Summer of 2024, Kris was actively promoting the regrowth of corals by developing coral nurseries, from which the corals could be replanted onto the reef. Reefs can be easily damaged by bad fishing practices, pollution, dropping anchors on the reef, or even severe storms. But in 2024, ten years of record global temperatures caught up Tarutao’s coral gardens.

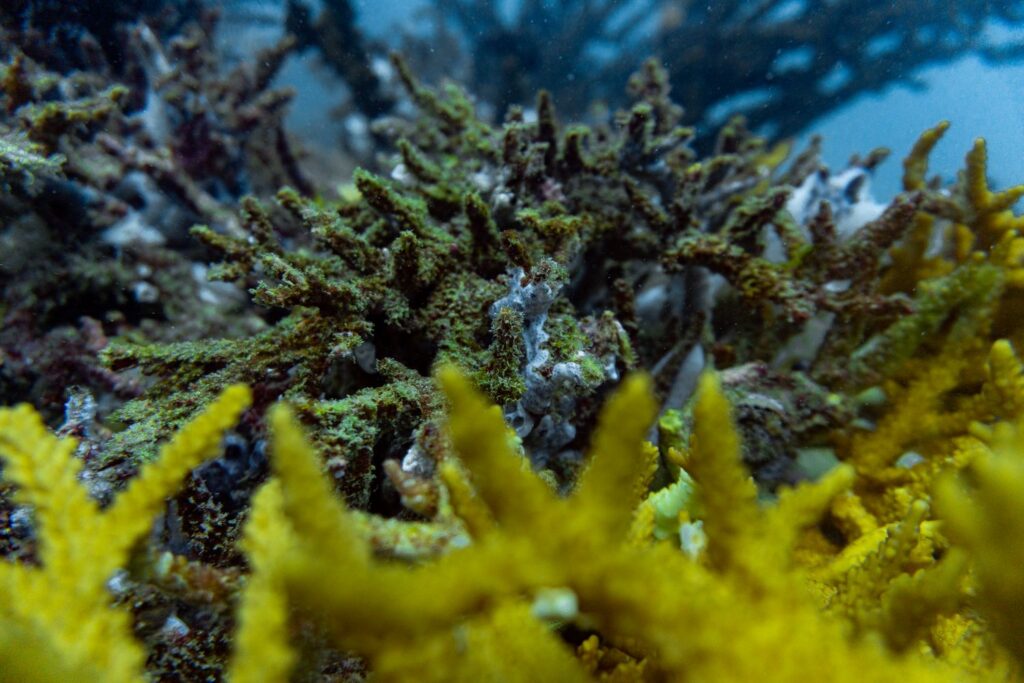

THE BLEACHING

‘From May, the sea temperature began to rise. We’re in the Straight of Malacca here, which produces strong currents and usually brings cooler waters, but this year the sea temperature rose to 34֯C! This is an incredible temperature, something I’ve never seen. Corals here bleach at around 31.5֯C (this is when corals expel Algae that are essential for their long-term survival, turning them white). The temperatures stayed high until September. I think we lost about 20% of the corals in Tarutao – including the ones I was growing in the nurseries…’

‘Were any of the corals affected worse than others?’ I enquire.

‘Many shallow reefs, with branching corals like staghorn, were really badly affected, but they also grow quicker. In some places they are already are beginning to recover.’

DEATH AND RENEWAL

This tallied with my own observations. Snorkelling off Sunrise Beach a few days before, I’d seen large swaths of now dead staghorn corals, but as I swam out to the reef drop-off, many of the larger brain, plate, and barrel corals seemed to be in good health. The soft corals also seemed to have avoided the worst effects.

‘Given time, the reef can recover. They are already recovering…but it takes time. My worry is that those same temperatures will return next year…’

I note that this prospect is ever more likely with the increasing pace of global warming. Whether corals can somehow adapt to conditions changing at such a dangerous speed is a question that marine scientists are puzzling over around the world. The signs are not encouraging…

THE SHARK MYSTERY

The Chow Ley are traditionally fishermen, and when the National Park was created in 1974, the local population was allowed to continue fishing. All other fishing is, in theory, prohibited. I ask about another disturbing sign I’ve noted on the reef – the lack of reef sharks.

‘There haven’t been many sharks here since I arrived…I assume that Chow Ley fished them all out…’ stated Kris.

To this, I observe that a healthy population of reef sharks is essential for the long-term health of the reef. Sharks pick off sick and injured fish and maintain fish populations in a healthy equilibrium across the reef. Would it be possible to introduce reef sharks back onto the reef? Kris is sceptical. Having said this, shark ‘re-introduction’ projects are in progress in other parts of the world.

A CONNECTION TO THE REEF

Sharks aside, Kris is generally positive of the Chow Ley’s fishing practices. ‘The Chow Ley rely on the reef, and understand it. They usually fish by placing box traps on the reef, with bait inside. Only limited amounts of fish are caught, and the rest of the reef is left undamaged.

Another benefit of tourism is that in the high season, most of Chow Ley are employed in tourism (including dive tourism) and there’s no need to fish. Fishing increases in the ‘off’ season.

Kris is also fairly easygoing on the national park authorities, who charge a fee to every tourist who visits these islands. They maintain a few patrol boats in the park and have fixed buoys at several diving sites to avoid anchor damage. The park also manages some basic camp/bungalow accommodation on Ko Adang, Ko Rawi, and Ko Tarutao.

ILLEGAL FISHING

But Kris also highlights the problems of illegal fishing, fishers who come from the mainland, or nearby Ko Libong. ‘They usually hide on the far side of islands, where they can’t be seen by the national park authorities or tourists. Many of these boats use much more destructive fishing methods than the Chow Ley, drift netting and trawling.’ Here too, Kris also highlights the positive aspects of tourism. ‘In high season the boats usually stay out of sight. If a fishing boat is spotted by a dive company, we can alert the authorities, so in effect, we act like an additional police force. Again, during the ‘off-season’ fishing boats become bolder, entering deep into the protected area, confident that they won’t be seen.’

‘Yep, your business depends on healthy reefs and good dive sites. No fish to see equals no business, so it’s 100% in the dive companies’ interests to protect the environment here.’

THE OCEAN HAS NO BORDERS

‘Fishing outside the protected area can also have an effect, for example at Eight Mile Rock. Eight Mile is an underwater sea mount South of Ko Lipe, famed for its pelagic sea life. Whale sharks and manta rays used to be relatively common. They are becoming much less so now. For species that migrate across the open ocean, such as whale sharks, relatively small protected areas do not provide the solution to the overexploitation of vast swathes of our seas.’

THE PLASTIC PROBLEM

I turn my attention to another negative aspect of tourism that I have noted on the island, plastic pollution and raw sewage. I note that behind many houses are huge piles of plastic waste. With nowhere on the island to bury it, it is simply chucked out or burned. I noted this when watching a water monitor in a pond behind a café, hunting for scraps amongst mountains of plastic waste. The wild meets the human reality of the 21st Century. It seemed a powerful metaphor for the state of our world today. Sewage is also a problem as tourist numbers rise, with no sewage treatment facilities on the island. This was not a problem with a community of a few hundred Chow Ley – but with thousands of tourists now visiting the island every year, this is becoming a major concern.

Kris acknowledges this problem but counterpoints it. ‘That’s true, and obviously, there are more resorts/bungalows going up all the time, but they also have an interest in maintaining their land…their stretch of beachfront. Most of the island’s beaches would be covered with plastic waste (most of which comes from the mainland) were it not for the hotels constantly cleaning up the beaches.’

A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE

Kris invites me to join him on some dives later in the week, where we will be replanting damaged/broken corals on the reef. He also advises me to contact Darius Vakili, who runs the Café Lipe on the island’s main beach, Pattaya. Darius runs weekly volunteer beach clean-ups around the islands and founded the Trash Hero movement. The clean-ups focus on a different beach each week. Darius is also one of the island’s oldest none native residents, having founded his business more than 20 years ago. During that time the island has changed a lot, from a near unknown backwater to a tourist hotspot.

DARIUS

Darius is a tall, serious, straight-talking man, and someone not inclined to hold back his true opinions. What is immediately apparent, sitting in the welcoming, leafy space of the café, is that he is far more critical of both the national park authorities and the environmental condition of the Tarutao National Park.

WHAT ONCE WAS

‘When I first came here, just snorkelling across the bay, you could see fifty reef sharks…now they’re all gone. The same is true for sailfish. You could see them, breaking the water, hunting in the bay…’ He gestures towards the bay, still beautiful, but crowded with longtail boats, yachts, and ferries. ‘There’s still some sailfish, but all the big ones, well they disappeared long ago.’

A PARK PROBLEM

As for the National Park authorities, who collect a fee from every tourist coming to Ko Lipe, and from every dive in the park, he believes that they are equally toothless. Unable or unwilling to properly police illegal fishing within the park, and also unwilling to deal with Lipe’s growing problems. ‘They had an offer to build a sewage processing facility on the island, but turned it down due to cost. They just want to keep the money for themselves.’

According to Darius, the park’s ecological woes aren’t just confined to below the waters surface. ‘The park allows, or refuses to control, illegal hunting on the islands. These islands used to be full of birds, but they’re being hunted by illegal wildlife traders and ending up in markets in places like Bangkok. Likewise, wild boar, and mouse deer, are being hunted for food. Selective illegal logging is allowed to take place.’

I found these accusations extremely disturbing. If true, it meant that not only was the park authority not doing a good job, but that potentially people in the park authority are actively profiting from illegal activity. A dark prospect indeed.

EIGHT MILES SOUTH

Each day I dived, exploring the island’s magnificent reefs. There’s so much to save here, so much beauty above and below the waves. One of the most spectacular dives, and certainly the most thrilling, is an exposed seamount, Eight Mile Rock, south of Ko Lipe near the Malaysian border (mentioned above, as the haunt of Whale Sharks and Rays). The dive is a true ‘Jaque Cousteau’ experience, with wicked currents, but huge congregations of marine life.

Diving with great barracuda, groupers, and clouds of reef fish at Eight Mile Rock. Video courtesy of my dive buddy on this adventure, Mr Yannick Meister!

Due to the danger of the current dragging us into the open ocean, we were forced to descend using a buoy line, pulling ourselves hand over hand, down into the deep. The seamount’s summit lies about 14 meters below the surface. As we descended it loamed out of the depths, a mass of rocks and boulders, covered in soft and hard corals, crowned with dense shoals of fish. With the current strong, we hid in the lee side of vertical rocks, exploring the canyons and crevices, but this was no easy dive. Each time we were exposed to the currents as we moved between the mountain’s twin marine summits, we had to fin with all our strength to make headway.

VISITORS FROM THE BIG BLUE

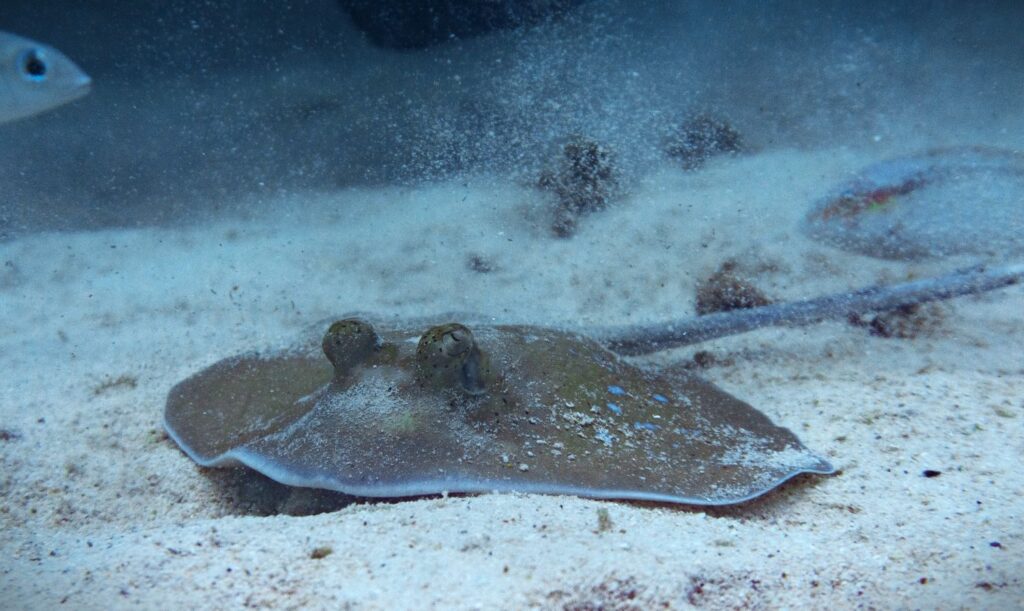

It’s worth it though…the sea here is alive, there are giant morays, yellow-edged morays, stingrays, and groupers. Above in the blue, congregations of great barracuda, Jacks, and trevally – open ocean predators, are waiting for a chance to snag some of the reef’s more unwary residents for lunch.

HOLD ON…

By the second dive, the current had increased further, to such a degree that none of us could move against it. We were left clinging on to sections of bare rock to avoid being swept out into the blue. The show comes to us…vast clouds of fish swirling around us humans, clumsy intruders into the underwater world. We were hoping for a whale shark or manta ray encounter, which didn’t materialize, but regardless, we all surface energized and inspired.

CORAL GARDENING

On my last day of diving, I head out with Kris to a couple of local dive sites, close to Lipe: Steps and Talang South. Before the bleaching Kris was using some of the spots here as coral nurseries. On this dive, he’s going to show me how small actions can help the reef in significant ways. Both being shallow reefs, sections of coral died due to the high sea temperatures. The idea is to look for corals that have been damaged or broken off and find them new homes in the cracks and crevices of the reef.

Kris explains ‘Often you’ll come across a coral…perhaps a fan coral or branching coral. It’s been smashed off the reef, and maybe it’s lying in the sand. If it’s left in that place it will die, but you can ‘transplant it’ to a new home, to the nooks and crannies on the reef. If it’s well placed, you’ll often find that in a couple of weeks, it has reattached itself to the reef and is thriving.’ To check that the coral is properly placed, he demonstrates a wave that he gives in front of the coral, to simulate the current. If the coral isn’t ‘blown’ from its new home, it will probably survive, he says.

WALKING THE WALK

Time to translate words into actions. We backroll into the warm water and descend to the reef. As expected, there are considerable areas of the reef that are dead or in poor health, but even here many beautiful corals survive. The marine life is still enchanting. Indeed, I get to see the only sharks during my time in Tarutao…A coral cat shark and nurse shark, both hiding (wisely) in caves on the reef, out of the way of fishermen.

THE MASTER AND THE STUDENT

Kris fins ahead of me gently, scanning the sandy areas in between rocky coral formations. He quickly spots a staghorn coral, broken away from the reef, lying in the sand. Demonstrating, he picks it up and inserts it in a likely looking hole in the reef. He gives the coral a quick, current-inducing wave, to make sure it won’t be swept back to the sand. It stays in its new home.

We continue and soon Kris is handing me bits of coral, and I’m inserting them, like a jigsaw puzzle, into likely looking holes. It’s incredibly satisfying work, thinking that these corals might well again be thriving on the reef, long after I’m gone. As we continue, I begin to get my eye in, spotting corals lying on the reef, diving down, and finding them new homes. As always, the reef’s residents are curious about our actions. A trumpetfish follows me cautiously for a few minutes, keeping its distance a few metres away, but obviously fascinated by this awkward bubble-venting alien…

THE CHALLENGES AND THE SOLUTIONS

The dives are over all too soon, and I return to the surface world with Kris. Cruising back towards Ko Lipe, the sun glittering on the azure sea, I consider what I have witnessed here. The Ko Tarutao National Park, its reefs, and forests are facing extreme threats, both directly, in the form of hunting, fishing, and pollution, and the massive global threat of climate change. Not enough is being done to address these issues, and they are beyond one person’s actions to fix…But many people, including Kris, Darius, and many in the local population, including the Chao Ley, are trying to make a positive difference.

BENEFITS FOR ALL

Local people also need to make money, like all of us. If we want the Cheo Ley, or any other people, to reduce fishing, they need another alternative. The diving industry can provide that. Likewise, divers can actively police the protected area, and, with good practices, actively play a part in restoring reefs.

All dive operators have an interest in maintaining dive sites in prime condition. No reefs mean no divers. I genuinely feel that divers can be part of the solution, protecting the reefs of the Andaman Sea and beyond, but it must be done in a thoughtful, sustainable way. As tourism has benefits, it also has a dark side, in the form of pollution, CO² emissions (from flights), and the sometimes destructive development we bring to these fragile places. Solutions need to be found for these pressing issues, better solutions than are currently in place. But progress can be made, if we all play our part – small as it might be.

LAST IMPRESSIONS

I didn’t want to leave Tarutao…the islands’ beauty and relaxed atmosphere were enchanting and addictive. As I sped away from Ko Lipe towards the mainland, images of the underwater world filled my mind: giant morays, having their teeth picked by delicate cleaner wrasse, the pulsating rainbow colours of squid and cuttlefish, elegant surgeonfish and Moorish idols, and fields of luminous corals waving in the current. Magical sites like these should be preserved for future generations, and our long-term survival as a species depends on the health of our home planet. I just hope these beautiful reefs are still thriving when I return.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Kris Scope, Farhan Jihem (Fas), Sean, and all the staff at Adang Sea Divers for their help and patience. They made this article possible.

Likewise, I would also like to thank Darius Vakili for sharing his insights into the changes he has witnessed during his time on Koh Lipe.

Adang Sea Divers runs excellent, environmentally conscious, small-group diving trips throughout the year. They also have accommodation on Sunrise Beach. You can contact them at: www.adangseadivers.com

Cafe Lipe offers excellent food and great value accommodation on Lipe’s Pattaya Beach. They also organise weekly beach clean-ups in the Tarutao National Park. Contact them at: www.cafe-lipe.com

To read more about conservation of our living world, check out these articles: